EU News

|

|

A european framework for simple and transparent securitisation

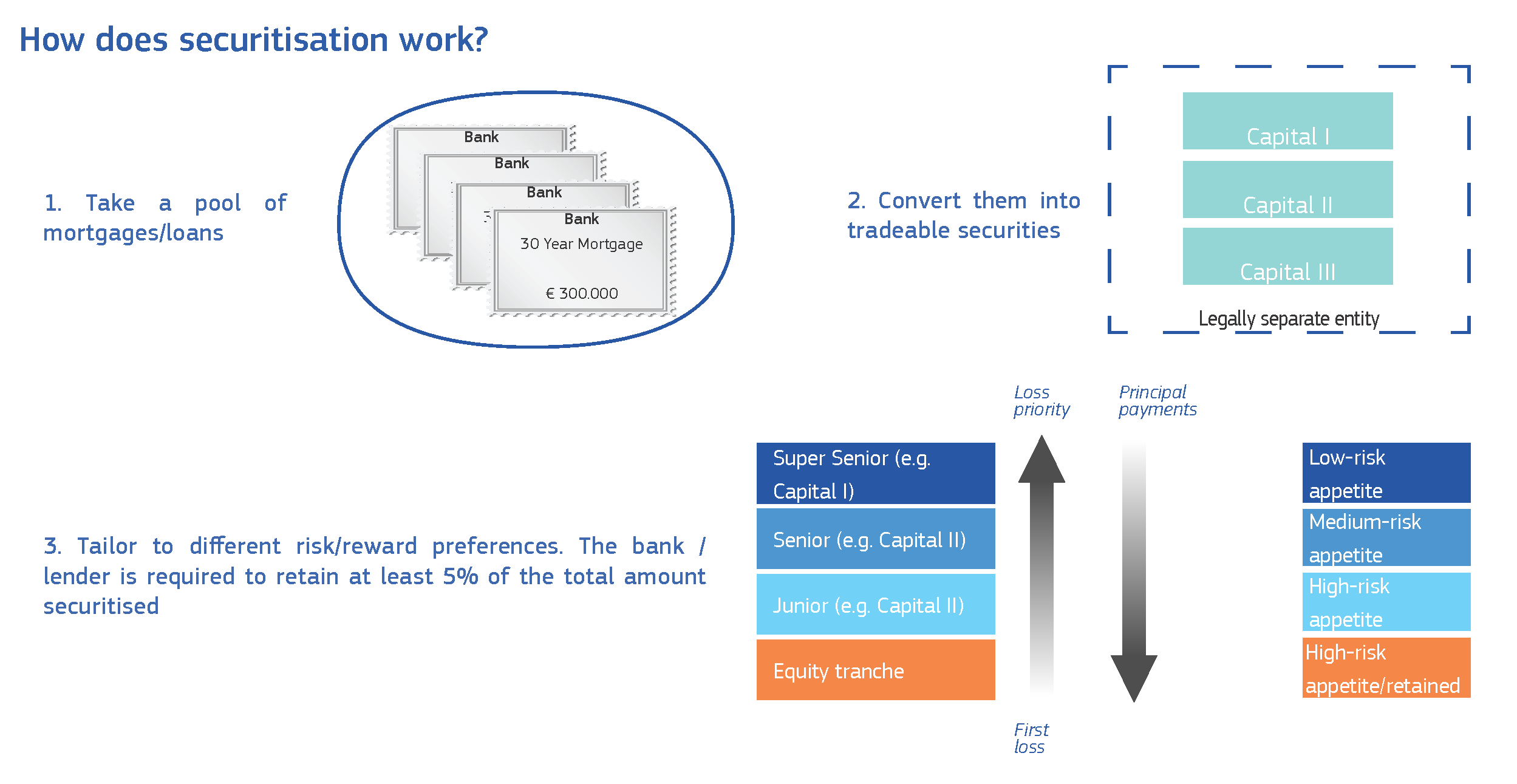

Securitisation is the term used to refer to a transaction that enables a lender – often a bank - to refinance a set of loans/assets (e.g. mortgages, auto leases, consumer loans, credit cards) by converting them into securities that others can invest in.

The lender pools a portfolio of its loans into a set of securities tailored to different investor risk/reward characteristics. End investors are then repaid by the cash-flows generated by the underlying loans.

The chart below depicts a typical mortgage securitisation:

Why does the Commission want to restart securitisation markets?

Soundly structured, securitisation is an important channel for diversifying funding sources and enabling a broader distribution of risk by allowing banks to transfer the risk of some exposures to other banks, or long-term investors such as insurance companies and asset managers. This allows banks to "free" the part of their capital that was set aside to cover for the risk in the sold exposures, thereby allowing banks to generate new lending.

This can be beneficial for:

- Businesses and households:

In the European financial system, where bank lending accounts for 75-80% of total funding of the economy[1], securitisation can lead to more credit for businesses and households. Securitisation can also provide additional investment opportunities by allowing banks to transfer assets to institutional investors (such as pension funds) to meet those investors' asset diversification, returns and duration needs. If EU securitisation issuance was built up again to pre-crisis average, it would generate between €100-150bn in additional funding for the economy.

For SMEs in particular, restarting securitisation markets would:

- help banks to free up capital that can then be used to grant new credit to firms, most of which are SMEs in the EU;

- foster issuance of asset-backed commercial paper products, which represent an important source of short-term SME financing;

- allow banks to securitise and therefore finance loans to SMEs more easily;

- encourage market participants to develop standardisation further. This in turn should reduce operational costs for securitisations. Since these costs are higher for the securitisation of SME loans than average, the drop in price should have an especially beneficial effect on the cost of credit for SMEs.

How are EU securitisation markets performing?

Since the beginning of the financial crisis, European securitisation markets have remained subdued. Recent public consultations by the European Central Bank and Bank of England[2], Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and International Organization of Securities Commissions[3] and the European Banking Authority[4] have highlighted the key factors limiting a sustainable recovery in securitisation markets. They include: the stigma still attached to this asset class, macroeconomic conditions (e.g. limited growth prospects), the availability of cheaper refinancing sources and regulatory uncertainties.

The slow recovery in EU securitisation markets reflects concerns among investors and prudential supervisors about the risks associated with the securitisation process itself.

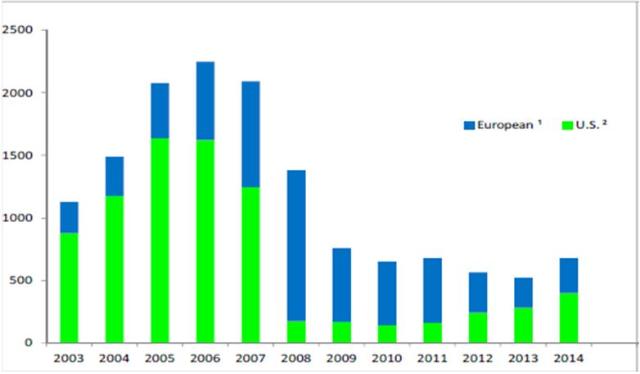

Securitisation markets in the US have recovered more strongly than in the EU. This has been mainly driven by the publicly-sponsored segments: almost 80% of securitisation instruments in the US benefit from public guarantees from the US Government Sponsored Enterprises (e.g. Fannie Mae and Freddy Mac). Banks investing in these products consequently also benefit from lower capital charges. Despite realising much larger losses during the crisis, this public support has helped the US securitisation markets recover faster than in the EU.

Figure 1 - Securitisation issuance in US and EU, USD billions

Source: International Monetary Fund

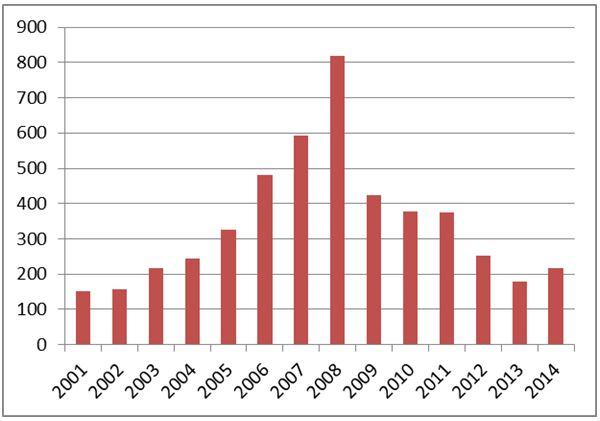

Securitisation issuance in Europe amounted to some €216 billion in 2014 compared to €594 billion in 2007. The issuance level of SME securitisations is only roughly half the amount prior to the crisis (€77 billion in 2007 compared with €36 billion in 2014).

Figure 2 - Securitisation issuance in the EU, €bn

Source: European Banking Authority

What is the state of play of discussions with the EU and globally?

A range of EU and international bodies have been undertaking work to help boost the market for securitisation. The joint paper and consultation responses by the Bank of England (BoE) and the European Central Bank (ECB) in May 2014[5] offer some useful avenues to explore. Moreover the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) are jointly leading a cross-sectorial Task Force on the impediments of securitisation. Its main task is to develop criteria to identify simple, transparent and comparable (STC) securitisation instruments.

Why is there stigma attached to securitisations?

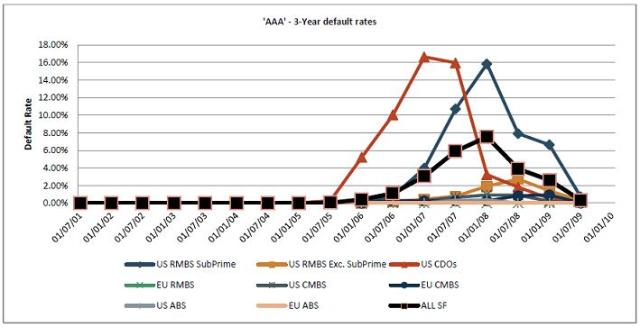

Securitisation of subprime mortgages created in the US contributed greatly to the financial crisis of 2008. Securitisations which, according to their credit ratings (AAA) should have had a 0.1% probability of defaulting, defaulted in 16% of cases and generated sizeable losses across the globe. As a consequence, investors lost trust in all securitisations.

Problems were, however, mostly limited to US markets and can be explained by a series of shortcomings:

- Giving loans and then selling them to third parties became a widespread practice. Therefore, the creators of such loans had no incentives to properly monitor the creditworthiness of the borrowers to whom they were giving credit. As a consequence, the riskiness of loans packaged in US securitisations increased in the run-up to the crisis. This "originate to distribute" model has been identified as a key factor in the US securitisation crash.

- The creation of ever-more complex securitisation structures (e.g. collateralised debt obligations (CDOs)[6] limited investors' understanding of such products and the risks attached to them. This, in turn, pushed investors towards relying excessively on credit ratings as the ultimate measure of riskiness. Credit rating agencies, for their part, were being paid to provide ratings for products whose complexity - as the 2008 events showed - defied their rating methodologies. Issuers, who charged high fees for issuing these products, had strong incentives to peddle such complex products.

- Limited disclosure of the details of the securitisation products made it even harder for investors to understand such complex products, further fostering overreliance on credit ratings.

How risky is securitisation?

The shortcomings highlighted above were not prevalent in EU markets. For example, EU issuers tended to retain a big part of the portfolio of the loans they packaged in a securitisation. Originate-to-distribute practices were almost non-existent in the EU. Overly complex structures such as CDOs and CDOs-squared were also rare in the EU, while widespread in the US. Such differences between US and EU practices had a clear effect on the performance of US and EU securitisation products during the crisis.

The worst-performing EU securitisation products rated AAA defaulted in only 0.1% of the cases at the height of the crisis. In comparison, their US equivalent defaulted in 16% of cases.

Figure 3 - Default rates of AAA-rated securitised products, EU vs. US

Source: European Banking Authority

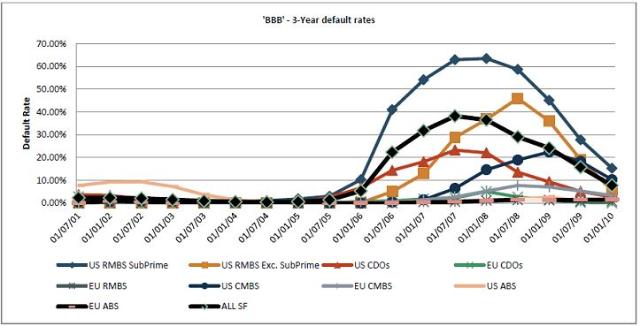

Riskier (BBB-rated) EU securitisation also performed very well, with the worst-performing classes defaulting in only 0.2% of the cases at the height of the crisis. By contrast, the default rate of BBB-rated US securities reached 62%.

Figure 4 - Default rates of BBB-rated securitised products, EU vs. US

Source: European Banking Authority

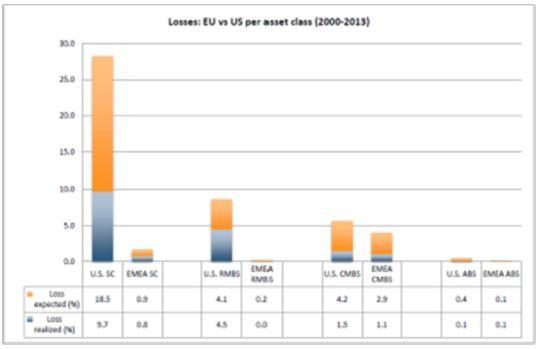

As a consequence, the losses incurred by investors in EU securitisations were a fraction of those incurred by investors in US deals. The drop in EU issuance cannot be ascribed to losses generated in Europe but rather to a combination of factors: stigma attached to securitisation, post-crisis tightening of the regulatory treatment of securitised products and cheaper funding alternatives for banks (central bank liquidity).

Figure 5 - Losses generated by securitised products, EU vs. US

Source: European Banking Authority

What is the objective of today's EU securitisation framework?

The proposed securitisation framework is a package including a Securitisation Regulation and amending the Capital Requirements Regulation.

The main objectives are:

- To revive markets on a more sustainable basis so that STS securitisation can act as an effective funding channel to the economy;

- To allow for efficient and effective risk transfers to a broad set of institutional investors;

- To allow securitisation to function as an effective funding mechanism for some non-banks (such as insurance companies) as well as banks;

- To protect investors and to manage systemic risk.

The overall objective of today's proposal is to promote a safe, deep, liquid and robust market for securitisation, which is able to attract a broader and more stable investor base to help allocate finance to where it is most needed in the economy. The European Commission does not intend to go back to the "bad old days" of opaque and complex subprime instruments which caused fire sales, price drops and illiquidity.

With its proposal, the Commission aims to differentiate between simpler and more transparent securitisation products and other products which don't satisfy such criteria. In the Commission's view, such differentiation should restore an important funding channel for the EU economy without endangering financial stability. The aim is to promote longer-term investors including non-bank institutions. It is also clear that this market is not for retail investors.

This initiative introduces a clear set of criteria to identify simple, standardised and transparent securitisation (STS), and aims to make securitisation sustainable.

Recent work by the European Banking Authority[7] (EBA) has shown how these criteria can help identify the type of securitisation that performed well and generated negligible losses during the crisis. Products satisfying such criteria have, indeed, suffered near zero default, while those not satisfying them suffered high default rates (12%).

Figure 6 - Default rates of securitised products respecting criteria of simplicity, transparency and standardisation (STS) vs. other securitisations

Source: European Banking Authority

What does 'simple, transparent and standardised' (STS) securitisation mean?

- 'Simple securitisation' means that:

- Assets packaged in securitisation must be homogeneous loans/receivables (e.g. car loans with car loans, residential mortgages with residential mortgages).

- No securitisation of securitisations is allowed.

- Loans must have a credit history long enough to allow reliable estimates of default risk.

- The ownership of a loan must have been transferred to the securitisation issuer (i.e. they must be sold by the creator of the loans to the entity that will issue the securitisation).

- 'Transparent and standardised securitisation' means that:

- Loans packaged in securitisation must have been created using the same lending standards as any other loan, no "cherry-picking" allowed.

- At least 5% of the loans portfolio must be retained by the originator.

- Documents must provide details of the structure used and the payment cascade (i.e. the sequence and amount of payments to each tranche)

- Data on packaged loans must be published on an ongoing basis.

- The contractual obligations, duties and responsibilities of all key parties to the securitisation must be clearly defined.

How can we ensure that an STS securitisation meets the qualifying criteria?

The issuer of the securitisation will need to confirm the instrument's compliance with all STS criteria and will communicate it to the European Securities Markets Agency (ESMA). This will imply that the issuer is legally responsible for any misreporting.

The Commission's proposal includes precise disclosure requirements from the originator, the sponsor and the issuer. These will be jointly responsible for providing to the investors all the relevant information needed to perform proper due diligence and assess the securitisation's riskiness. It is also required that these data are included in a website, following standard templates, and will be accessible to investors. The proposal includes provisions already set out in previous legislation that require the gathering of relevant data in a securitisation-dedicated website.

What is the role of competent authorities?

As securitisation involves several actors (originators, sponsors, issuers, investors, etc.), it is important to clarify which authority will be responsible for the supervision of each party. For the sake of simplicity and legal clarity, the authority with oversight of a specific party will have responsibility for the securitisation activities undertaken by that party. For example, the banking supervisor of a bank originating the loans packaged in a securitisation will be responsible for supervising the securitisation activities undertaken by this bank.

As each securitisation can involve parties from different sectors (banking, insurance, asset management.) and different countries, competent authorities will communicate and collaborate in order to find common approaches on securitisation matters.

How will an investor know how to identify an STS securitisation?

Upon communication by the issuer to ESMA, the instrument will be listed in a centralised web data repository listing all STS securitisations. This website will be accessible to all investors for free.

Does the proposal provide for sanctions in case of wrongdoing?

Sanctions are provided for in case of wrongdoing by any party involved in the securitisation process. This is essential for the functioning and the credibility of the system.

In particular, if a competent authority ascertains that a securitisation previously considered STS does not fulfil all STS requirements, the product will be removed from the website listing STS products and a financial sanction will be imposed on the originator (minimum €5 million, or up to 10% of the annual turnover of the legal person or other similarly large sums). The originator may also be banned temporarily from issuing STS products. Member States also have the possibility to introduce criminal charges but they are not obliged to do so.

Are 'synthetic' securitisations (instruments that use derivatives to transfer risk) included in the proposal?

Synthetic securitisations carry additional legal and counterparty risks that need to be taken into consideration, and. As a consequence, some of the more complex synthetic products generated much higher losses than those generated by simple and transparent structures.

Precise criteria to identify more simply synthetic securitisations are being developed by the European Banking Authority and the Commission stands ready to consider the inclusion of any such criteria developed.

What is the Commission proposing in terms of the prudential treatment of securitisation for banks and insurance companies?

Today's securitisation proposal recognises the different risk profile of STS and non-STS securitisations. As a result, the Commission will amend the current prudential treatment for both banks (Capital Requirements Directive) and insurance companies (Solvency II) in order to establish a closer relationship between the riskiness of a securitisation and the prudential capital required from banks and insurance companies investing in it.

Why does the securitisation proposal amend banks' prudential treatment (i.e. Capital Requirements Regulation) but not that of insurance companies (i.e. Solvency II)?

This is simply an issue of sequencing of the regulatory changes that are required. Although the Commission is empowered to adopt changes to the Solvency II Delegated Regulation in order to amend insurers' prudential treatment for securitisations, new calibrations would have to be set out in a legal text that would refer to the Securitisation Regulation proposed today, in particular regarding the STS requirements. As a result, the necessary changes to the Solvency II Delegated Regulation can only be adopted after the Securitisation Regulation has been adopted. The Commission intends to ensure that the new calibrations in the insurance and banking sectors will apply as from the same date.

How will the revised framework for securitisations by banks contribute to enhancing economic growth and job creation?

The new, more risk-sensitive provisions on regulatory capital requirements and the introduction of specific criteria for STS securitisation will make investing in safer and simpler securitisation products more attractive for credit institutions established in the Union and release additional capital for lending to enterprises and households. Historically, credit institutions have been the main investors in European securitisations. In the future, the CMU’s objective is to expand the investor base of Union securitisation markets by making it more attractive for non-bank investors to fund securitisation exposures. Nevertheless, it is likely that credit institutions will form a large part of securitisation’s investor base in the EU.

What are the next steps?

The securitisation framework proposed today will be transmitted to the European Parliament and the Council for adoption under the co-decision procedure. As with any other EU Regulation, its provisions will be directly applicable (i.e. legally binding in all EU Member States without transposition into national law) as from the day of entry into force.

For more information see also IP/15/5731

http://ec.europa.eu/finance/securities/securitisation/index_en.htm

[1] See "Bank deleveraging, the move from bank to market-based financing, and SME financing", OECD 2012. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-markets/Bank_deleveraging-Wehinger.pdf

[2] See https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecb-boe_case_better_functioning_securitisation_marketen.pdf

[3] See http://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d332.htm

[4] See https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/846157/EBA-DP-2014-

[5] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecb-boe_case_better_functioning_securitisation_marketen.pdf

[6] A collateralized debt obligation (CDO) means that the pooled assets – such as mortgages, bonds and loans – are essentially debt obligations that serve as collateral for the CDO.

[7] https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/950548/EBA+report+on+qualifying+securitisation.pdf

.gif)