RUSI

|

|

The Ukrainian Crisis and the Integrated Review

While the UK has played an active role in responding to Russian aggression on the foreign policy front, there is more to be done to protect the many civilians now at risk in Ukraine.

It seems a lifetime ago, but in March 2021 the UK government published its Global Britain in a Competitive Age white paper, known colloquially as the Integrated Review. The inference behind the notion of integration was that the UK’s security, defence, development and foreign policy assets would act in concert and not in isolation from one another. As the only CEO of a major UK NGO who has also served in the Army, I welcomed the prospect that some of these barriers might be broken down.

My charity, the Halo Trust, works in 28 of the most difficult countries in the world and employs 10,000 staff. Two of these countries have dominated the news headlines since the Integrated Review was published. In Afghanistan, Halo employs 2,500 staff clearing improvised explosive devices and other explosive remnants of war. The Integrated Review and the accompanying merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office with the Department for International Development came too soon for comfort during the Afghan crisis. Halo has been able to continue working in Afghanistan, but the UK is making almost no use of its ability to stabilise the country through the clearance of improvised explosive devices, the employment of ex-fighters in peaceful capacities and the management of huge stockpiles of ammunition and small arms. With the prospect of the UK being ruthlessly focused on Europe for the foreseeable future, it is time that NGOs such as my own – light-touch and inexpensive – were put to use further afield.

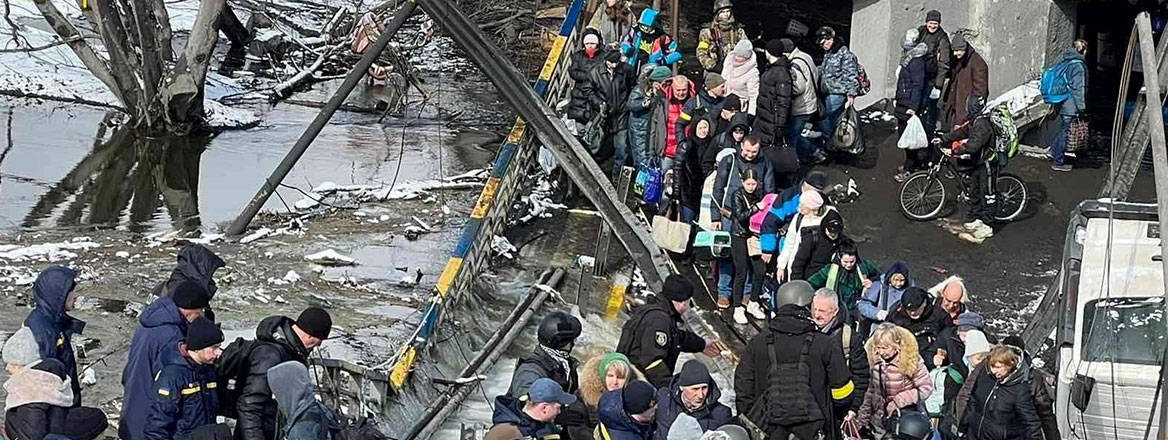

In Ukraine, the Halo Trust has employed 450 staff in Donbas since 2016. Despite the appalling circumstances of the last weeks, Halo remains one of the only UK NGOs still functioning in the country. Halo, which exists to destroy lethal munitions, has unparalleled visibility of the scale and intensity of the violence currently being meted out on the people of Ukraine. In densely populated cities, indiscriminate use is being made of cluster munitions, scatterable mines, thermobaric bombs, rocketry and conventional artillery. Halo lost all contact with its staff in Mariupol for 36 hours and has since received one short text message: ‘No communication, no water, no electricity, no food in stores. Ships, artillery, planes are shooting. The population is already on the edge. But we're holding on. I have no words, this is a living hell’.

Russian armour and infantry, at first on the edges of cities, have begun fighting into urban centres with devastating consequences for the innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. As I write, Halo’s Ukrainian national staff are bravely seeking to offer humanitarian support through first aid, the provision of information about explosive types and the clearance of unexploded ordnance. The sad truth is that a once-coherent workforce of 450 staff is rapidly being fragmented by the chaos of war as communications are cut, the internet fails and darkness falls on cities.

Worrying as the situation is, I am not writing this article to add to those rightly lauding the courage of Ukraine’s people. Instead, I want to signpost how the Integrated Review should be applied in Ukraine. While this crisis has struck with even greater speed and ferocity than events in Afghanistan last August, I sense that UK ministers and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office have been more sure-footed in their response. The UN, the G7, the EU and other countries have condemned Russia’s actions, and the UK has taken a leading role. An unprecedented array of economic and other sanctions has been imposed, targeting Russia’s finance, energy and military-industrial sectors, as well as individuals and sporting events. In addition, governments have bolstered arms supplies to Ukraine to support its defence.

Led by ministers, the UK has played a full and honourable part in this process. The prime minister’s six-point plan published on Sunday is a good start, but it now needs to be fleshed out into something much more substantive. To that end, ‘integration’ is really the act of writing a campaign plan that brings together all lines of operation, whether civilian or military, for a common purpose.

Protecting Western Ukraine

Winston Churchill’s quip that ‘You can always count on the Americans to do the right thing, after they have exhausted all the other possibilities’ is true of all of NATO. The trouble is, there is no time to exhaust all the other possibilities. Moreover, public option is shifting from hoping that war can be avoided to wanting to actively help Ukraine.

The right thing now is for the West to protect the millions of Ukrainians at risk from the conflict by helping Ukraine establish bastions in the west of the country. The justification for this is clear: Putin has broken the Budapest agreement, which exchanged Ukraine’s nuclear weapons for guarantees of security, just as Kaiser Wilhelm II breached Belgian neutrality in 1914. The difference in 2022 is that while the UK had no fear of a nuclear German Empire in 1914, Putin still has the warheads that Ukraine renounced.

The right thing now is for the West to protect the millions of Ukrainians at risk from the conflict by helping Ukraine establish bastions in the west of the country

The West is therefore wary of direct military confrontation and fears talk of no-fly zones or safe havens. So far, the UK and NATO are being reactive and painfully proper. NATO is using the rhetoric of sympathy, not defiance, and has thereby ceded the initiative to Putin. It is only his military incompetence that has stopped him from exploiting that initiative. The Western Allies are obsessed with avoiding escalation and direct conflict. This merely confirms to Putin that he has the entire domain of conventional warfare and the whole Eurasian landmass – except for NATO territory – in which to do as he pleases.

To restore momentum, the West should enable the establishment of two bastions: one around Odesa in the south, and the second around Lviv. The defence of Odesa will be vital to prevent a link-up with Transnistria and to deny Putin domination of the Black Sea coast. Lviv must be protected as the alternative capital and to guarantee safety to millions of Ukrainians seeking sanctuary.

This does not require the insertion of NATO ground troops or the use of Western air power. Instead, a gigantic logistics operation should be initiated, akin to the Berlin Airlift, in which as many anti-aircraft systems, anti-tank systems and other ordnance are transferred as soon as possible. There is not long to achieve this, and the evidence suggests a maritime assault on Odesa is coming soon.

NATO should quickly make clear the legal grounds based on the responsibility to protect and the fact that the support comes at the request of the Ukrainian government. Moreover, NATO must communicate clearly that the defences are credible. The Ukrainians have already rattled Putin into thinking that he might not have the full room for manoeuvre that he assumed. The Ukrainian impact on the Russian Army’s morale is already significant. Putin is running out of troops to control the east and centre of the country before he has even secured Kyiv and Kharkiv. The news that Russian troops would have to fight for western Ukraine could be decisive in causing a collapse of morale.

Failure to establish the two bastions mentioned above would transfer the possibility for confrontation onto the borders of NATO – with Article 5 implications – and would mean that perhaps as many as 10 million Ukrainians would enter the EU. So, allowing the Russians to close up to the borders of NATO might appear less risky, but would in fact be fraught with risk in the long term.

Ameliorating Suffering in Central and Eastern Ukraine

The UK government needs to fund Explosive Ordnance Risk Education (EORE) for internally displaced persons (IDPs). From Halo’s experience of working in Myanmar, mass displacement in a conflict or post-conflict zone can result in high levels of accident, injury and death. With the possibility of safe corridors opening up, people – notably children – passing through or temporarily staying in areas littered with the explosive residue of war are unlikely to understand the technical details of munitions and are often acutely vulnerable.

Hazard mapping and survey paves the way for other humanitarian actors. A lesson learned from Kosovo – where Halo conducted the initial survey in 1999 – and the numerous phases of conflict in Afghanistan is that it is just as important to identify safe areas as it is to point out hazardous ones. Survey allows IDPs or refugees to travel down safe corridors and move to safe areas; it also enables other humanitarian and government actors to re-establish themselves and commence their work.

Explosive clearance saves lives. Risk education and hazard mapping should be followed as soon as possible by explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) and munition clearance to remove the source of risk. This saves lives and enables areas to be reoccupied. The UK is the world’s leading country in the delivery of EOD, and its skills should be put to full use.

The sheer scale of what is developing will likely dwarf any comparable humanitarian crisis in recent history, and be on our own European doorstep

By virtue of its nuclear power and heavy industry, Ukraine poses a significant radiological and chemical hazard. This threat applies not only to its own people, but as Chernobyl demonstrated, it can easily extend to all of Western Europe and eastwards into Russia. As with its EOD capacity, the UK leads the world in its ability to respond to chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats. The recent fire at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant throws this need into sharp relief. The UK should be ready to despatch an emergency response capability into any locally negotiated ceasefire at any vulnerable sites.

Shelter, Water, Sanitation and Food in Poland and Other Bordering Countries

The sheer scale of what is developing will likely dwarf any comparable humanitarian crisis in recent history, and be on our own European doorstep. During the Kosovo crisis, a smaller mass migration of ethnic Albanians caused the UK government and its allies to adopt a genuinely integrated approach, with civilian and military agencies working in close concert.

In 1999, the UK appointed a senior officer, the then Brigadier Tim Cross, to take responsibility for the humanitarian effort, establishing and maintaining refugee camps in Macedonia and Albania. He was tasked with commanding multinational troops, as well as coordinating the humanitarian efforts of personnel from the UK Department for International Development, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and multiple NGOs.

Speaking about his experience, he later called it a ‘challenging and demanding deployment’ and ‘the first time that I have come face to face with a large-scale humanitarian crisis’. He went on to say that the most challenging part was the military working alongside large numbers of civilian agencies and that the Army needed to learn how to work better with such organisations.

Over 1.7 million people have already fled the fighting in Ukraine, and forecasts suggest that European countries bordering Ukraine will be overwhelmed by a tide of Ukrainian refugees unless the full resources of the West are applied to alleviate their suffering. UN agencies and NGOs will not have the capacity to address this crisis, and nor does the traditional cluster system have sufficiently effective command and control arrangements. With key countries such as the US, UK and Canada being outside the EU, it may be appropriate (as in the Kosovo example) for NATO to underpin the UN with its own command and control capability, backed by logistical and engineer support.

Command and Control

This article does not cover the Article 5 requirements of the Alliance to bolster defences in bordering states, notably on the northern flank in the Baltic, as well as in the eastern Balkans. In central Europe, the UK should offer the NATO-assigned Allied Rapid Reaction Corps to command the multi-agency response in Ukraine. There would also be sense in appointing a civilian supremo to act as a coordinator between the UK military and civilian effort.

In conclusion, all Defence reviews suffer from the fate of being overtaken by events, and the Integrated Review is perhaps the most spectacular example of this. It is for others to judge the wisdom of pivoting to the Indo-Pacific and disbanding the Army as an organisation capable of fighting war at a large scale. But in one regard at least, the Integrated Review got things right: this crisis covers the full spectrum of civil and military challenges, and never has a situation demanded a more integrated response. We must set the conditions for success in what is fast becoming the defining foreign policy challenge of our lifetimes.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

Original article link: https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/ukrainian-crisis-and-integrated-review

.gif)