Climate Change: The perfect fuel for wildfires?

22 Sep 2020 12:29 PM

As wildfires continue to rage in North and South America, Met Office Chief Scientist Professor Stephen Belcher examines what has led to the potentially record-breaking scale of fires and what science is needed to contain the risks.

California firefighters tackling one of many wildfires which have raged across the eastern United States during 2020. Pic: Shutterstock.

Last year wildfires ravaged Australia. This year has seen reports of extensive fires in the Amazon, in California, and earlier this year during the hot spell, also in the UK. Even the area within the Arctic Circle is experiencing an extraordinary fire season, with thawing permafrost exposing large areas of carbon-rich peatlands, acting as additional fuel and a huge new source of greenhouse gas emissions. And it’s not just that we are seeing more in the news about wildfires, data shows the number of fires is increasing. By May this year, the number of wildfires recorded in South America was already higher than in any previous year since systematic monitoring began in 1998. And since the early 1970s, California’s annual wildfire extent has increased fivefold.

Wildfires are more severe during extended periods of hot dry weather, because higher temperatures cause more evaporation and that dries the vegetation, creating fuel for the fires. For example, last year, Australia saw very hot, dry, conditions caused by a pattern of temperatures in the Indian Ocean, known as the in Indian Ocean Dipole. The Indian Ocean Dipole is a natural fluctuation in the climate that affects the weather patterns around the world including in Australia, but now this fluctuation is adding onto a world that is warmer because of climate change.

So now that the globally-averaged temperature has risen to more than 1.0°C warmer than in the pre-industrial world, it is not surprising that we are seeing more wildfires around the world. Importantly though, higher temperatures alone will not necessarily lead to more fires. Fuel must be available and there needs to be an ignition source, either by human influence or lightning strikes. Climate change may also lead to wetter conditions in some places, as warmer air can hold more moisture, which can affect fuel availability and flammability.

In January this year, an international group of scientists, including from the Met Office, got together to survey the published scientific evidence and concluded there is consistent evidence that hot dry weather conditions promoting wildfires are becoming more severe and widespread due to climate change.

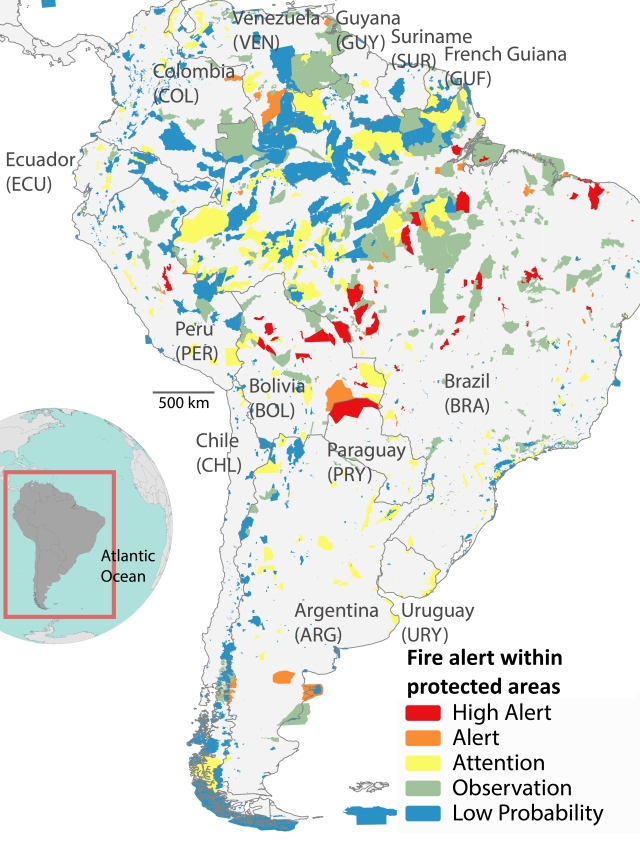

So, we are going to continue to experience more wildfires as the climate changes. This is driving a need to provide forecasts that trigger fire prevention to limit accidental fires. At the Met Office we now produce forecasts of a ‘fire severity index’ for England and Wales. And earlier this year, scientists from the Met Office and from CEMADEN and INPE in Brazil, developed a technique to assess the likelihood of high fire conditions across South America during the riskier months of August to October. This is part of a broader move from traditional forecasting of weather into forecasting the impacts of weather.

Map of South America showing status of fire alert within protected areas

Chantelle Burton a Climate Scientist at the Met Office who specialises in wildfire research, said: “By using computer simulations of the climate now, with the present-day levels of carbon dioxide, and comparing with computer simulations of the climate with pre-industrial levels of carbon dioxide, we can calculate how climate change has increased the chances of hot weather spells. These techniques are now being extended to calculate the role of climate change in increasing the chances of wildfires.”

Wildfires also pump additional carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, so can act as a ‘positive feedback’. So, as the world warms, we expect more wildfires, that will further warm the climate. Putting numbers on this is a difficult task. Pioneering recent research at the Met Office has combined outputs from vegetation and climate models, paving the way for future climate projections to include wildfires.

If we are to meet the ambitious Paris Climate Agreement to keep global warming to below 2.0°C degrees above pre-industrial levels, then we must cap our atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Additional release of carbon dioxide from wildfires reduces yet further the volume of fossil fuels that can be burnt whilst keeping global warming in line with the Paris Agreement. There are other natural processes that are likely to emit additional greenhouse gases into the atmosphere as the climate warms, for example permafrost melting in Siberia. But it’s all about numbers now. A high priority for climate science is to put numbers on these positive feedbacks through better measurements and improved computer models of the climate system so that we can plan for a future that keeps global warming to within the lowest possible limits.