How lockdown affected children’s stress and anxiety

30 Sep 2020 11:49 AM

Children’s lives changed beyond recognition when full lockdown began on 23rd March. With schools shut to the majority of pupils, the regular rhythms of childhood and adolescence – from school runs and playtime, to exams, celebrations and graduation – were put on indefinite hold.

Anecdotally, we know that many children struggled with the demands of home learning and with loneliness after weeks of social isolation. Vulnerable children faced real hardship as a result of Covid-19, in particular children in care and custody, those with disabilities or mental illness, those at risk of abuse or without a permanent home. However, for many children with a stable home environment, lockdown brought some welcome respite from the everyday stresses of school, bullying and peer pressure.

As the Covid-19 crisis unfolded, the Children’s Commissioner’s Office wanted to understand in greater detail how school closures and weeks at home had affected children’s levels of stress and anxiety. We therefore conducted surveys of around 2,000 young people aged 8-17 in England in March and June, to establish the frequency and causes of children’s stress in lockdown.

How often did children feel stressed during lockdown? (June survey)

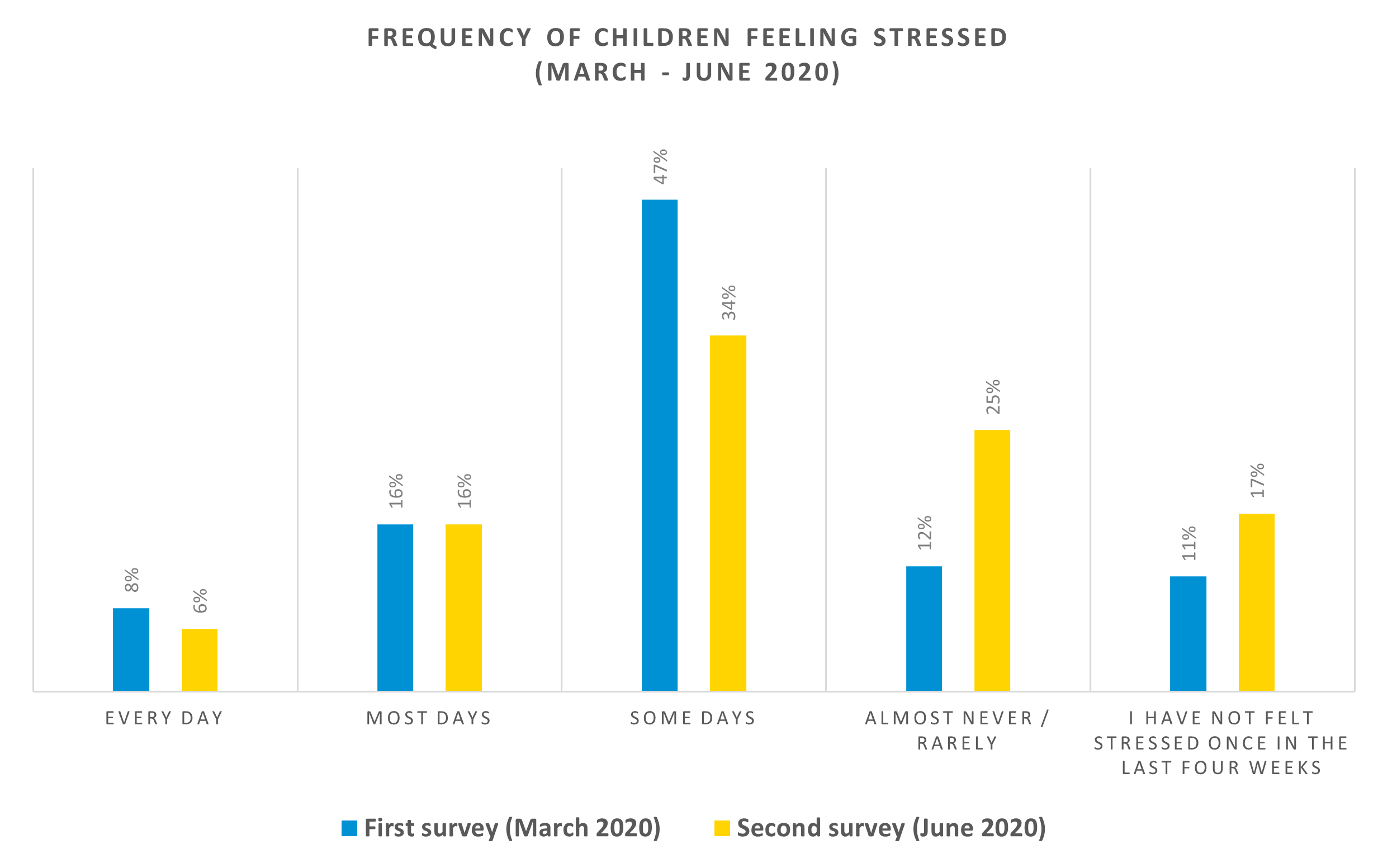

Contrary to what may have been expected, the surveys found that many children felt stressed less frequently as lockdown progressed. The percentage of children feeling stressed some of the time decreased from 47% to 34% between March and June 2020, while the percentage of those feeling ‘rarely or ‘never’ stressed rose substantially from 23% to 42%.

The reason behind the fall in some children’s stress levels through lockdown is still open to speculation. Some insight comes from children’s free text answers to our question ‘what makes you feel stressed?’. In the first survey, answers were diverse, including school, big crowds, anxieties about appearance, bullying, gaming and even allergies. In the second survey answers almost exclusively centred around coronavirus, with very few exceptions. We can hypothesise that the elimination of these ‘extra little’ everyday worries left some children feeling less stressed during the pandemic.

Another answer may be found in the timing of our first survey (13-27th March), a period of particular public crisis and confusion as lockdown was announced and schools closed indefinitely. The overall reduction in stress may have been a natural result of lockdown becoming ‘normalised’, and therefore less of a source of stress for most children.

However, it is worth noting that the number of children reporting persistent stress – everyday or most days – remained consistent between the surveys, around 22-24%. Children whose parents were unemployed at the time of the June survey were most likely to experience persistent stress, 29% of whom reported feeling stressed most or every day.

Persistent stress is a predictor for common mental health diagnoses – including depression, anxiety, OCD and panic disorder. Persistent stress, and wider mental health problems, unlike ‘small, everyday’ stresses, would not necessarily have been eliminated by lockdown. In fact, YoungMinds found that the coronavirus pandemic worsened the condition of 80% of young people with a history of mental health needs. Therefore, it should perhaps be no surprise that our surveys found a consistent number of children experiencing persistent stress at the beginning and at the end of lockdown.