Older children are getting wise to fake news

29 Nov 2017 02:50 PM

Older children are less trusting of news on social media than from other sources, and employ a range of measures to separate fact from fiction, Ofcom research has found.

- Social media is popular news source for tweens, but not all trust it

- Nine in ten older children would check whether news on social media is true

- More younger children online than ever before, including half of pre-schoolers

- YouTube brand more recognised by older kids than BBC One and ITV

- Ofcom launches review of children’s television and on-demand content

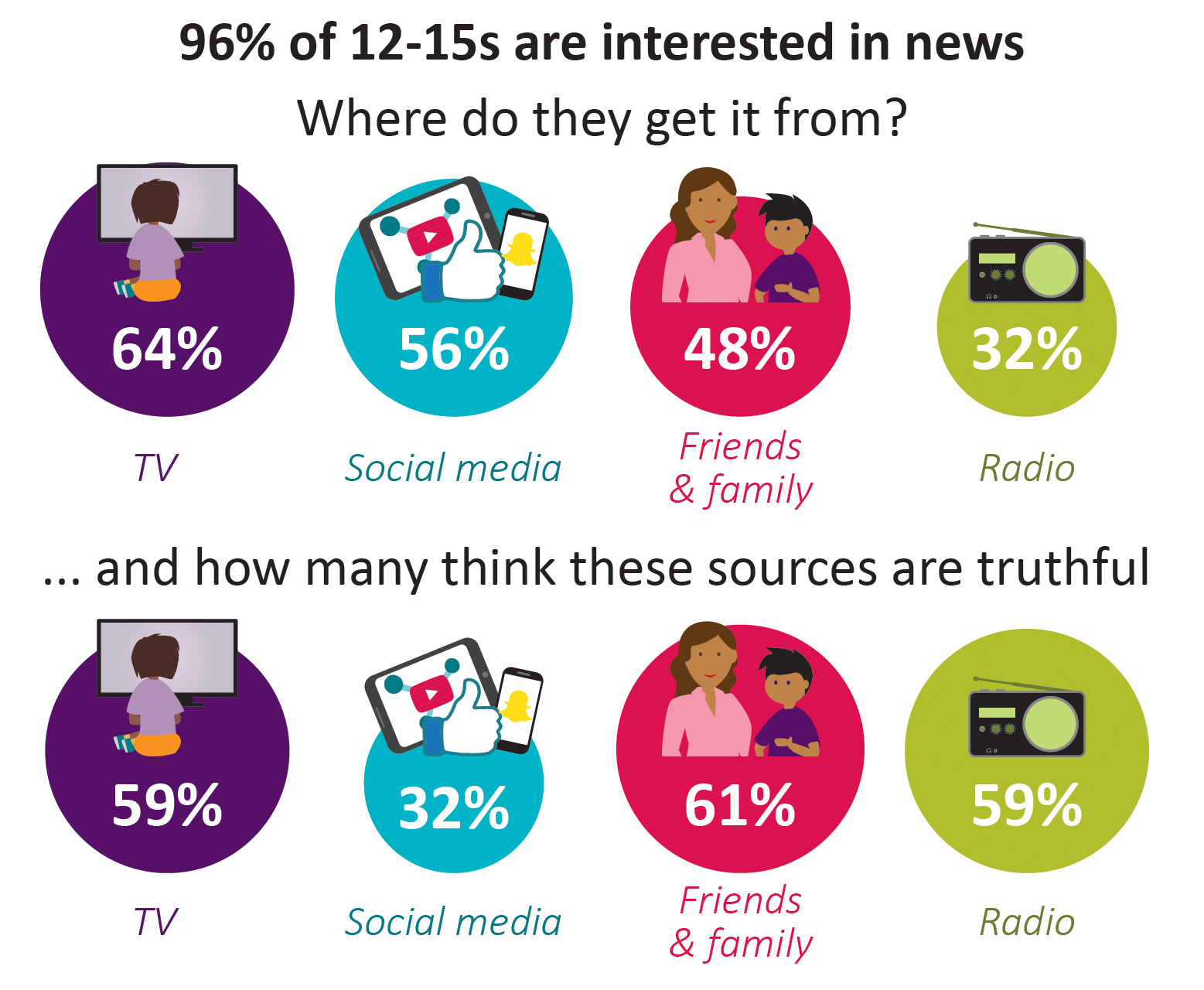

More than half (54%) of 12- to 15-year-olds use social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, to access online news, making it the second most popular source of news after television (62%).

The news that children read via social media is provided by third-party websites. While some of these may be reputable news organisations, others may not.

But many children are wise to these risks. Just 32% of 12- to 15-year-olds who say social media is one of their top news sources believe news accessed through these sites is always, or mostly, reported truthfully, compared to 59% who say this about TV and 59% about radio.

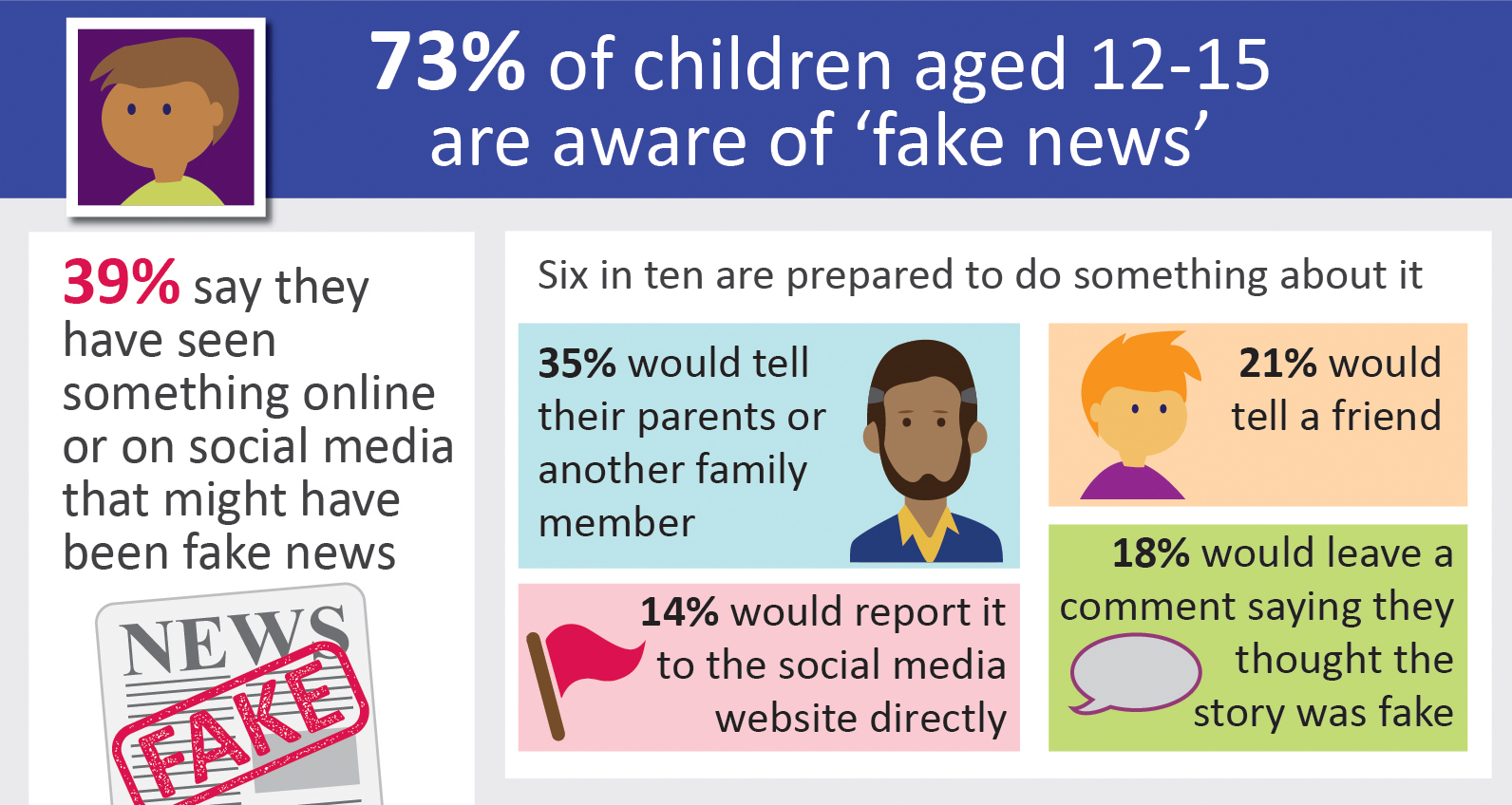

Nearly three-quarters (73%) of online tweens are aware of the concept of ‘fake news’, and four in ten (39%) say they have seen a fake news story online or on social media.

The findings are from Ofcom’s Children and Parents Media Use and Attitudes Report 2017. This year, the report examines for the first time how children aged 12 to15 consume news and online content.

Filtering fake news

The vast majority of 12-15s who follow news on social media are questioning the content they see. Almost nine in ten (86%) say they would make at least one practical attempt to check whether a social media news story is true or false.

The main approaches older children say they would take include:

- seeing if the news story appears elsewhere (48% of children who follow news on social media would do this);

- reading comments after the news report in a bid to verify its authenticity (39%);

- checking whether the organisation behind it is one they trust (26%); and

- assessing the professional quality of the article (20%).

Some 63% of 12- to 15-year-olds who are aware of fake news are prepared to do something about it, with 35% saying they would tell their parents or other family member. Meanwhile, 18% would leave a comment saying they thought the news story was fake; and 14% would report the content to the social media website directly.

But some children still need help telling fact from fiction, almost half (46%) of 12-15s who use social media for news say they find it difficult to tell whether a social media news story is true and 8% say they wouldn’t make any checks.

Emily Keaney, Head of Children’s Research at Ofcom, said: “Most older children now use social media to access news, so it’s vitally important they can take time to evaluate what they read, particularly as it isn’t always easy to tell fact from fiction.

“It’s reassuring that almost all children now say they have strategies for checking whether a social media news story is true or false. There may be two reasons behind this: lower trust in news shared through social media, but the digital generation are also becoming savvy online.

Children’s online lives

More children are using the internet than ever before. Nine in ten (92% of 5- to 15-year-olds) are online in 2017 – up from 87% last year.

More than half of pre-schoolers (53% of 3-4s) and 79% of 5-7s are online – a year-on-year increase of 12 percentage points for both these age groups.

Much of this growth is driven by the increased use of tablets: 65% of 3-4s, and 75% of 5-7s now use these devices at home – up from 55% and 67% respectively in 2016.

Children’s social media preferences have also shifted over recent years. In 2014, 69% of 12-15s had a social media profile, and most of these (66%) said their main profile was on Facebook. The number of 12-15s with a profile now stands at 74%, while the number of these who say Facebook is their main profile has dropped to 40%.

In contrast, Snapchat has rapidly grown in popularity among this ‘tween’ group. More than three in ten (32%) say it’s their main social media profile, up from just 3% in 2014.

Though most social media platforms require users to be 13 or over, they are very popular with younger children. More than a quarter (28%) of 10-year-olds have a social media profile, rising to around half of children aged 11 or 12 (46% and 51% respectively).

Awareness of the required minimum age is low among parents. Six in ten parents of children who use Facebook (62%), and around eight in ten parents of children who use Instagram or Snapchat (79% and 85%) either didn’t know there was an age restriction, or gave the incorrect age.

Many parents choose not to apply minimum age limits. Among parents of children aged between 5 and 15, over four in ten (43%) said they would allow their child to use social media sites ahead of them reaching the minimum age required.

One reason for this could be that nearly all parents of 5-15 year olds (96%) say they mediate their children’s use of the internet. This includes having regular conversations with their child about online safety, using technical tools such as network-level filters, imposing rules about internet use, or directly supervising their child. Two in five parents (40%) use all four methods.

More parents of children aged 5 to 15 are using network-level filters at home – 37% did so last year, nearly twice the level in 2014.

Aside from social media, one of the primary online destinations for children of all ages is YouTube, with eight in ten (81%) children aged 5 to 15 regularly using the website to watch short clips or programmes.

Among older children, YouTube is the most recognised content brand; 94% of 12-15s have heard of it compared to 89% for ITV, 87% for Netflix, and 82% for BBC One and Two.

Negative online experiences

Half of children (49%) aged 12 to 15 who use the internet say they ‘never’ see hateful content online.[1] But the proportion of children who have increased this year, from 34% in 2016 to 45% in 2017.

More than a third (37%) of children who saw this type of content took some action. The most common response was to report it to the website in question (17%). Other steps included adding a counter-comment to say they thought it was wrong (13%), and blocking the person who shared or made the hateful comments (12%).

Review of children’s content on television

The research shows that most 8- to 15-year-olds believe there are enough programmes on television for children their age, and the content suitably reflects their lives.[2]

But some 8- to 15-year-olds disagree. One third (35%) of 8- to 11-year-olds who watch TV say that not enough programmes show children that look like them; while 41% of 12-15s say that too few programmes show children living in their part of the country.

Building on this research, Ofcom yesterday launched a Review of Children’s Content[3]. We will examine the range and quality of children’s programmes across TV broadcasters and content providers, and highlight any areas of concern.

The review will consider three broad areas:

- Audience behaviour and preferences. What content do children watch, and how do they access it? We will also look at what children think about the range and quality of the content currently available.

- The availability of children’s programmes. What content are television broadcasters and other content providers making for children? This will include programmes from public service broadcasters, commercial television channels, on-demand and streaming providers.

- Incentives to invest in children’s content. What are the incentives and disincentives for broadcasters to invest in children’s content? We will consider how these factors affect the quality and range of content available.

Ofcom is inviting initial input to the review by 31 January 2017. We will publish our findings, alongside any proposed regulatory measures, in summer 2018.

Notes to Editors

- ‘Hateful content’ means ‘something hateful on the internet directed at a particular group of people, based on, for instance, their gender, religion, disability, sexuality or gender identity’.

- The majority of 8-11s and 12-15s say there are enough programmes for children their age (76% and 65% respectively), and enough programmes showing children doing the sorts of things they or their friends do (63% and 54%).

- This review will help us decide how, and if, we might use the new power provided in the Digital Economy Act 2017 which enables us to publish criteria for children’s programmes and, if appropriate, set conditions for the licensed public service broadcasters (Channel 3 services, Channel 4 and Channel 5).

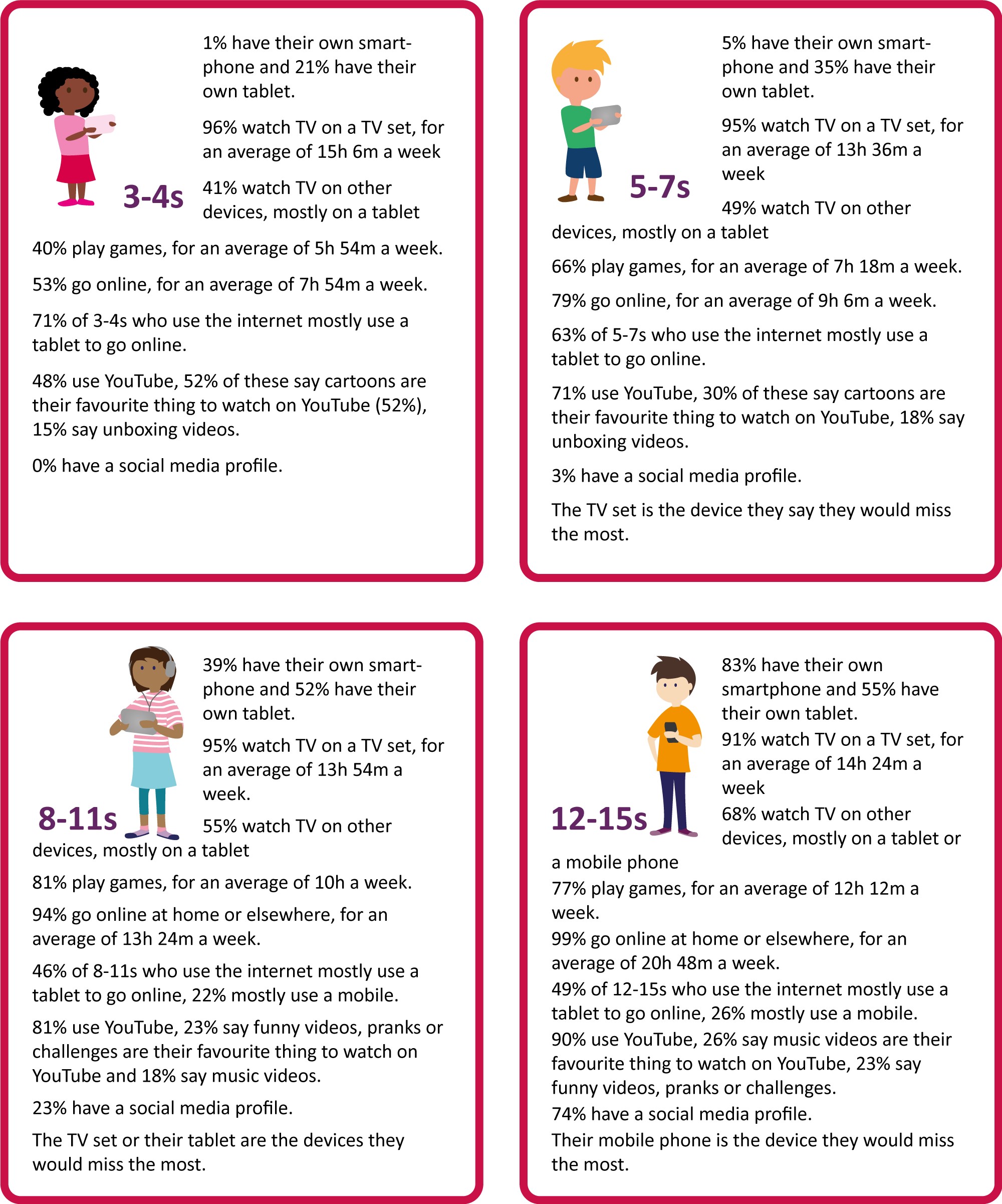

Media lives by age: a snapshot