The state of child poverty and how we can tackle it Home > Latest

17 Oct 2019 12:21 PM

On the United Nations Day for Poverty Eradication we should never fail to be shocked that we are talking about child poverty when are one of the wealthiest countries on earth.

Yet as all of us here know, the number of children living in poverty has been steadily increasing in recent years.

There are around 4 million children in the UK growing up in poverty. And those poverty rates have risen for every type of working family – lone-parent or couple families, families with full and part-time employment and families with different numbers of adults in work.

This is the first time in two decades this has happened, and incredibly it is happening at a time of rising employment.

As Children’s Commissioner for England, I meet children from all sorts of backgrounds. Some of the children I meet from the poorest parts of the country are doing well. Not every single child growing up in poverty is unhappy, doing badly at school or at risk.

But the evidence is clear – poverty can make existing vulnerabilities worse. Growing up in poverty puts at risk the building blocks of a good childhood – secure relationships, a decent home and an inspiring education.

Alongside the day-to-day anxieties about finances and the strained relationships that can cause within families, and the missing out on many of the childhood experiences other children enjoy, there are long term consequences. The fact is, if you grow up in poverty you have fewer opportunities to live a healthy, prosperous life.

The impact of poverty is clear from an early age – nearly half of the children who receive Free School Meals don’t have a good level of development.

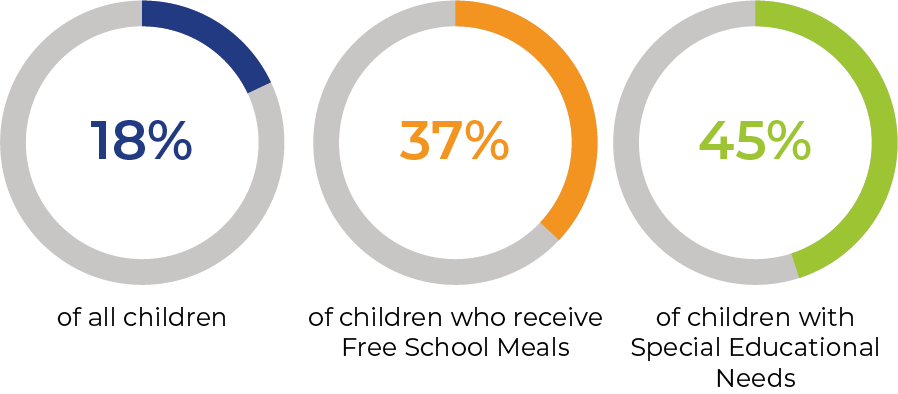

And a child living in poverty is more likely to lag behind at school and to leave education with poorer qualifications. My office has published research showing that one in five children are leaving education without even the most basic qualifications. Nearly four out of ten – 37% – of children who receive free school meals leave education without a Level 2 qualification.

Children who leave education at 18 without reaching Level 2 attainment

Children from more deprived areas are also more likely to go into care, and children in custody are far more likely to have been eligible for Free School Meals than the general population.

So the consequences of failing to tackle child poverty are clear. If we accept that millions of children are growing up in poverty, we are accepting the problems that go with it – poor outcomes, poor health, poor prospects, social problems that end up costing billions to deal with.

It’s my job to shine a light on these experiences – like the thousands of children who spend years of their childhood in unsettled temporary accommodation.

A couple of months ago, my office published a report looking at the number of children in England living in families who are homeless.

The figures are stark. 120,000 children in England are living in temporary accommodation. There are also 90,000 children living in families who are ‘sofa-surfing’.

Of course the label ‘temporary’ is sometimes anything but. In 2017, around four in ten children in temporary accommodation – that’s around 50,000 children – had been there for at least six months. Around one in twenty had been there for at least a year.

And of course this accommodation is usually terrible…

B&Bs where sometimes the bathroom is shared and there is nowhere to cook. Places where vulnerable adults can be living on the same corridor.

Office block conversions – individual flats the size of a parking space, where families live and sleep in the same single room.

And even converted shipping containers – cramped and airless – hot in the summer, freezing in the winter.

One child told us “we have to eat on the floor as there’s no enough space … when we sleep water drips on us which we don’t like.” A teenage boy described living in a hotel for 8 months alongside sex workers. We spoke with children who are spending hours every day having to get to and from school because they have been housed far away from where they are taught. Others told us that being homeless can lead to bullying and causes stress and tensions within their families.

Something has gone very wrong with our housing system.

These are children whose families are trapped by increasing rents and an unforgiving social security system. It’s a cycle that many families just cannot break out of it, and it is leaving some with no other choice than to rely on food banks.

I cannot tell you how heart-breaking it is to go on a school visit and to find that there is actually a food-bank in the school itself. A few weeks ago I met two children introduced to me by CBBC’s Newsround – they told me that they didn’t know what would be in the cupboard during the school holidays when they weren’t receiving their school meal.

And this is all happening in the context of cuts to service provision – 60% cuts to Sure Start and universal services over the past 10 years, for example – so we have poorer children growing up in neighbourhoods deprived of resources that can help compensate for that poverty.

If all of this sounds hopeless – it doesn’t have to be. There are changes that can be made that would make an immediate difference, and there are investments that need to be made to tackle the long-term problems of child poverty.

This should be a moral endeavour for every government, regardless of its political persuasion. Overcoming poverty is a huge challenge – but previous governments have done it, in particular by providing help to low paid working families.

So the next Budget could make changes to Universal credit – scrap the two-child limit, benefit cap and the five week wait for first payments. We also need to restore the value of benefits, so that Universal Credit’s achievements can in fact help to reduce poverty. The continued roll-out should be paused until the full impact on child poverty is reviewed and addressed.

I also want to see investment in early years provision which can help to close the gaps between children growing up in poverty and other children.

Yet I’ve heard more from politicians about HS2, water renationalisation and tax cuts – and, of course, Brexit – than about children.

We should be ashamed that there are literally millions of kids in England not having the childhood a decent society would want.

A million children – around four in every school class – need help for mental health problems. Over 50,000 children aren’t getting any kind of education, while nearly 30,000 are in violent gangs. Many more are growing up at risk due to family circumstances. These are young carers; kids living in households where the adults are involved in substance or drug abuse, mentally ill and violent. Not all of them are poor but many are. Often they are the children who bear the brunt of cuts in public spending and services rationing.

And while the additional spending on schools is welcome, it won’t solve these problems.

Our manifesto for children published last month is my plea to politicians to make children a priority – particularly the poorest.

I want to see all the political parties signing up to its aims.

Firstly – extend and expand the Troubled Families Programme, delivered through a network of family support centres in the most deprived areas, building on existing children’s centres and extended school opening hours – helping families not only with very young children but as their children grow up.

Secondly, a Child and Adolescent Mental Health counsellor in every school.

Thirdly, adequate funding for SEND pupils, including pre-statutory support.

Fourthly, I want to see schools open at evenings, weekends and holidays to provide a range of activities from sport to arts, drama to digital citizenship, and high quality youth support. The benefits would be wide-ranging, would broaden access to education, and help families on low incomes with childcare. None of the cost of this should be borne by schools or teachers.

And I want to see the next Government establish a cross-government Cabinet Committee for children.

Alongside all of this, and changes to Universal Credit, we need more affordable social housing so that children aren’t having to live in shipping containers and converted office blocks.

I don’t pretend that tackling all of these complex generational problems will be quick or cheap – in fact it will cost billions.

But millions of families are working night and day just to get by, juggling their childcare, ending up with hardly anything to show for it – and they need some help.

I want England to be a great place for all children to grow up. For many it is. But it can only be for all if politicians choose to make it happen. I will continue to challenge them and to pressure them to do so for as long as I’m the Children’s Commissioner.

*** A keynote speech given by Anne Longfield at the London Child Poverty Summit on the United Nations Day for Poverty Eradication. The summit was held by The Childhood Trust and the London Child Poverty Alliance and aims to bring together those working with and taking responsibility for supporting London’s disadvantaged children and young people in order to explore the causes, consequences and solutions for child poverty.